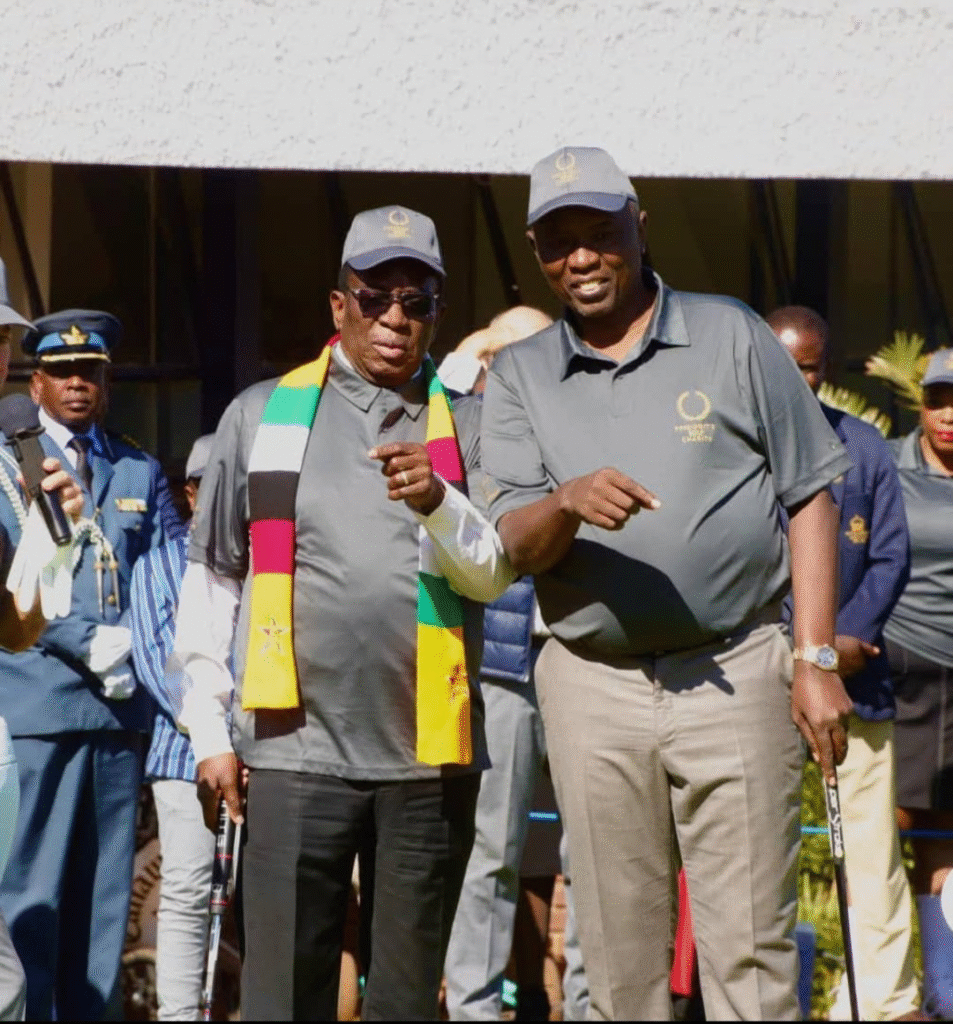

CALM BEFORE THE STORM: MNANGAGWA’S 2030 GAMBLE TEARS ZANU PF APART

A political storm is brewing within Zanu PF. As President Emmerson Mnangagwa heads into the party’s annual conference set for 13–18 October in Mutare, he faces a dangerous choice: push forward with his controversial 2030 agenda, or retreat and leave his ambitions buried under rising party tensions.

Mnangagwa has three options. He can call for a referendum—or possibly two—risking a humiliating public defeat. He can try to use Parliament to postpone the 2028 election and sneak in an unconstitutional term extension. Or, he can abandon the idea altogether and accept the 2028 constitutional limit on his presidency.

Publicly, Mnangagwa insists he won’t stay beyond 2028, claiming he is a “constitutionalist.” But last year, he rallied Zanu PF to pass a resolution at the Bulawayo conference allowing him to run beyond his second term. That alone exposes the double game he’s playing. The real motive isn’t just power—it’s fear.

Mnangagwa doesn’t want his deputy, Constantino Chiwenga, to take over. The man who helped orchestrate the 2017 coup that brought Mnangagwa to power is no longer the preferred successor. Mnangagwa suspects Chiwenga would not protect him or his family. Worse, he fears Chiwenga might go after their wealth and possibly prosecute them for corruption and looting. Trust is gone.

The succession crisis isn’t just personal. It’s ethnic. After Mugabe’s long rule as a Zezuru, Mnangagwa and his camp believe it’s time for a Karanga-led era. They don’t want another Zezuru like Chiwenga at the helm. In Zimbabwe, ethnicity still shapes who gets what, and who rules. It’s the ugly truth of our politics.

As the succession race intensifies, new players are creeping in.

Kudakwashe Tagwirei, the shadowy business mogul and Mnangagwa ally, has presidential ambitions he denies. But his allies say otherwise. With deep pockets and political backing, Tagwirei believes money can tip the scales. Yet Chiwenga has blocked him from entering Zanu PF’s Central Committee, where real power is negotiated between congresses.

Then there’s Chris Mutsvangwa, the loudmouth Zanu PF spokesperson. He also claims he doesn’t want the presidency. But few believe him. His recent positioning suggests he sees an opening—one he may try to exploit.

And in the shadows stands General Philip Valerio Sibanda, commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces. A quiet operator. A man of strategy. Last December, Mnangagwa tried to push him into the politburo during the Gweru conference, but was blocked on constitutional grounds. Still, the plan to make him a successor is not dead. Sibanda is expected to retire at the end of the year, and with that, the political door opens.

The struggle for power is no longer between founding nationalists like Nkomo or Mugabe. That era is gone. Mnangagwa represents the second wave—those who sat behind the giants. But now, power is shifting to the ex-combatants. Chiwenga leads that charge. Sibanda follows close behind.

Some say Sibanda stands no chance. Chiwenga is ruthless and determined to take power—by any means. Others argue Mnangagwa may take the ultimate risk and fight to install Sibanda as a loyal successor. The stakes are high. One wrong move, and the entire Zanu PF structure could collapse in on itself.

Since Mugabe’s removal in 2017, Zanu PF has been bleeding from internal power struggles. What was once a united front is now a snake pit of factions, betrayals, and fear. As October approaches, one thing is clear: this is the calm before the storm—and everyone inside the ruling party knows it.